Upcoming changes in EU online payments and what they mean for security

The EU is introducing major updates to online payment regulations, including PSD3, PSR, Verification of Payee, Instant Payments and eIDAS. This article explains what these changes require and how they will impact mobile onboarding, transaction authorization and fraud prevention across financial systems.

This article is a follow-up to my previous article about transaction authorization problems in the current banking ecosystem. Today, I will explore upcoming regulatory changes in the EU and check if they will significantly raise the bar for attackers.

I will discuss: PSD3/PSR, Verification of Payee, Instant Payments, and eIDAS. Most of these changes will be required within 1-2 years; however, since they’re significant, financial app owners might consider implementing them earlier to gradually update their systems rather than doing everything at once.

In the previous article, I’ve shown that mobile app is a huge usability vs security problem for financial systems. If an attacker can pair a mobile device controlled by them with a victim’s account, they can do anything – order transfers, authorize transactions, change limits, etc. Pairing an attacker device is not trivial but possible using phishing and clever social engineering tricks, and this tactic is widely used by attackers nowadays. I’ve also discussed potential solutions to this problem. However, let’s check if upcoming regulations will help prevent these fraudulent scenarios.

Connect with the author on LinkedIn!

PSD3/PSR

The Payment Services Directive in version 2 (PSD2) was a good direction. It ordered all payment service providers to implement Secure Customer Authentication (SCA), which is basically 2-factor authentication, mandatory for all users. That was a true game-changer. Without this regulation, there would be endless discussions in project teams about whether users would accept the inconvenience for increased security.

Unfortunately, on mobile devices, this regulation was overinterpreted, and we have ended up with a de facto one-factor authentication approach. Why? Because biometry and possession factors are delegated to the smartphone subsystem, as I discussed in my previous article. If an attacker can pair their device with the victim’s account, they have control over all authentication factors and, more importantly, over transaction authorization as well.

PSD3 and PSR (Payment Service Directive and Regulation) are introducing some positive changes that could lower fraud risk, but definitely it’s not a silver bullet for all problems.

* Current PSD2 will be replaced by PSD3 (Payment Services Directive) and PSR (Payment Services Regulation). PSR will replace the technical part of the previous PSD2, and PSD3 is more about the legal aspects of financial systems. Both PSD3 and PSR are currently in the EU legislative process, so all my analysis is based on the current versions as of the end of October 2025.

Activation of a mobile device

PSR requires strong customer authentication and the use of separate communication channels when a mobile application is activated on a new device remotely (Art. 51, paragraph 5). In addition, the activation must be delayed by at least four hours before it becomes fully active. Users can later opt out of this delay, but the first remote activation will still be subject to it.

This is an important change because it can reduce the effectiveness of attacks where an attacker pairs their own phone with the victim’s account. However, it only works if the user notices that something is wrong during the delay period. For that to happen, other security measures must be in place, such as clear notifications and confirmation with the user that they really want to activate the new device. Such notifications are also required by PSR (Art. 51, paragraph 5a).

Changes to SCA

In the upcoming version of the payment directive regulation (PSR), requirements when PSPs shall apply strong customer authentication have been extended to include new use cases (PSR, Art 85):

- (1.b) Where the payer “accesses payment account information online” – This is a functional change, headed towards better adoption of open banking and Account Information Services.

- (1.c1) Where the payer “orders the creation or replacement of a token of a payment instrument via a remote channel” – This is a significant change which secures the process of e.g. ordering a new payment card or pairing the new phone. However, it’s aligning the regulation requirements with common sense and the current state of the art. In my practice, following the adoption of PSD2 in 2010, I’ve not seen a single implementation of e-banking or e-payments where equal or more secure authorization mechanisms do not protect the change or ordering of a new payment instrument as those used for everyday transactions. Those operations should be protected much more than ordinary transactions because they are highly prone to fraud and relatively infrequent, so inconvenience should not be a significant problem.

- Also point (d) which in PSD2 was rather general – “any action (…) which may imply a risk of payment fraud or other abuses”, now in PSR is more precise: Where the payer “carries out any other action, through a remote channel, which may imply a risk of payment fraud or other abuses, including, but not limited to, increasing their spending limits, changing their password online, changing their contact information online“. In my opinion, it should also include changing notifications. Disabling notifications is a standard action during fraud.

- MOTO transactions (mail and telephone orders) are surprisingly excluded from SCA. In my opinion, it creates a wide path for fraudsters to bypass SCA. Transaction authentication, e.g., on a mobile app or through SMS, without any exemptions, when it’s technically possible, would promote secure behaviour. In the case of MOTO transactions, it will not be overly abusive for the user and the market.

- Article 85a of the PSR adds another exemption from using SCA – when “the payer initiates the transaction following a request issued by the merchant”. It’s for one-click transactions during e-shopping that are not protected by additional authentication. Only the creation of a 1-click process between the merchant and the payer is subject to SCA. The EBA shall develop Regulatory Technical Standards to specify the conditions under which this exemption applies. I hope that it will require PSP to have some form of ever stronger authentication than in the case of a single transaction.

- During the legislative process, a dispute arose over an idea to allow two authentication factors from the same category (e.g., fingerprint and face, or two forms of OTP or two passwords) if they are “technically independent.” Fortunately, in the current draft of PSR, these changes were abandoned.

Transaction monitoring

PSR requires transaction monitoring based on risk and allows exemption from SCA, but precise requirements will be defined in the upcoming EBA Regulatory Technical Standards.

Sharing fraud-related info between PSPs

PSR encourages banks and PSPs to share fraud-related info. Nowadays, most banks share current fraud information, but the directive will enforce it. In the event of new fraud scenarios, PSPs will be able to act more quickly. And hopefully they will.

Refund rights in more fraud scenarios

PSD3 introduces broader refund rights for fraud victims, which is a positive step toward consumer protection. However, this change also places significant pressure on Payment Service Providers (PSPs), who are already operating in a complex and high-risk environment. While the goal is to safeguard users, even those with limited security awareness, the reality is that PSPs often struggle to balance compliance, fraud prevention, and operational costs. Currently, many fraudulent transactions go unresolved, leaving users to pursue lengthy court proceedings. Additionally, the “gross negligence” clause remains problematic, as its interpretation can vary widely, creating uncertainty for both consumers and PSPs.

Verification of Payee (VOP)

Verification of Payee is part of the Payment Services Regulation, but it will be mandatory even before PSR, as it is a requirement for SEPA instant payments introduced in 2025. Technically, it is a considerable change. During credit transfer, PSPs must verify a match between the payee’s name and unique identifiers (e.g., IBAN) and notify the payer of any discrepancies. The PSP of the payer will send to the PSP of the payee a request to verify IF the IBAN matches the name of the payee as given by the payer. Responding PSP will check if the account number and the name match and provide the response using the” traffic light” system:

- Match – The name aligns with the account number.

- No match – Display a clear mismatch warning to users before proceeding.

- Close match – Minor discrepancies detected, requiring user verification.

- Check is not possible – Service unavailable or technical issues.

This response is passed to the payer, who will then be responsible for deciding whether to make the transfer. That aims to prevent impersonation scams or invoice fraud. But most importantly, it will help to reduce simple user mistakes during transfers.

In my opinion, it is a move in the right direction, but it has significant flaws:

- The most crucial one is the delegation of the final decision to the user. It’s highly susceptible to social engineering, and I’m concerned that attackers will quickly adapt their techniques and convince victims to accept a mismatch. In this case, the PSP is generally not liable for the loss caused by the accepted transfer.

- It’s technically complicated. It requires APIs between PSPs. And like any complex technology, it could be prone to vulnerable implementations. We will explore this as soon as we can test the first implementations.

- And, finally, it will not help to stop all fraudulent scenarios. Especially in the case of pairing an attacker’s phone with a victim’s account, the attacker will still be able to initiate and accept any transfer. Exclusion of liability in case of VoP mismatch makes users potentially even more vulnerable.

Connect with the author on LinkedIn!

Instant Payments

The SEPA Instant Payments Regulation, effective from 2025 in the Eurozone and from 2026 in all EU countries, is transforming European banking security by mandating that euro credit transfers be processed in under 10 seconds, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. This shift to real-time payments introduces significant cybersecurity challenges, as there is no time for traditional fraud detection or transaction reversals, increasing fraud risks up to tenfold, according to an EBA analysis.

Banks and payment service providers must upgrade their IT infrastructures to meet the rigorous PSD3/PSR requirements, such as real-time verification of payees (VoP, as described above), sanctions screening, and enhanced fraud detection.

eIDAS 2.0

eIDAS 2.0 establishes a comprehensive framework for electronic identification and trust services across the European Union. The regulation mandates that all EU Member States provide citizens with free digital identity wallets by December 2026. Regulated sectors, including banking, financial services, telecommunications, and healthcare, are required to accept these wallets by 2027. Key components of eIDAS are:

- Electronic Identification (eID): Standardized digital identity verification across EU borders.

- Trust Services: Including electronic signatures, seals, timestamps, and authentication certificates.

- European Digital Identity Wallet (EUDI): A Mobile application storing citizens’ credentials verified by the government.

The changes introduced by eIDAS and their impact on regulated sectors are so extensive that they warrant a separate article and thorough analysis. Here, I want to summarize key implications for financial system security:

- SCA Integration: The regulation complements PSD/PSR requirements by providing cryptographic authentication. Banks can delegate authentication to EUDI wallets, and the wallet will give the identity factors required by SCA – e.g., “something you have” (the wallet) with “something you are” (biometrics).

- KYC Processes: EUDI wallets enable instant customer verification without manual document checks, reducing onboarding friction while maintaining security. Banks can verify customer identity using government-backed credentials rather than relying on physical documents in various languages.

- Transaction Integrity: Qualified Electronic Signatures (QES) ensure digital transactions have the same legal validity as handwritten signatures, reducing the risk of contract fraud. Banks can attach electronic seals to all customer documentation, providing authentication guarantees, or can use QES as a transaction authentication mechanism.

- Reduced Identity Theft: eIDAS implements cryptographic verification, making identity fraud significantly more difficult compared to traditional document-based systems.

Of course, all of these are just promises, and their success will heavily depend on the implementation of EUDI wallets and the correctness of the integration between the eID wallet and banking, payment, or e-commerce systems. The nature of these systems is quite complicated, and implementation is prone to errors; moreover, they should be thoroughly analyzed and tested for potential vulnerabilities.

In the past, our team has identified significant vulnerabilities in the implementation of EUDI wallets. We are now researching the security of European Digital Identity systems as part of the CYSSDE grant.

Summary

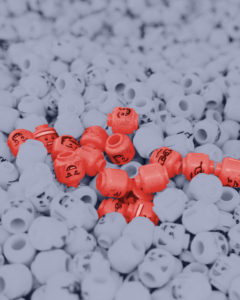

Banks and financial institutions are facing the imminent introduction of numerous regulations and new system integrations. A big challenge is implementing all these changes within a similar timeframe while ensuring that the entire security framework remains cohesive and prepared for evolving attack techniques. Attackers will not resign, and they will adapt their methods in response to changes introduced by PSD3, PSR, VoP, and eIDAS. They will also exploit new opportunities arising from instant payments and changes in APIs. Therefore, regulatory compliance alone will not be enough to stop fraud.

Banks, fintechs, payment operators, and other entities within the financial ecosystem must continuously analyze fraud risks, stay up to date with emerging attack techniques, adapt their defenses to ever-changing conditions, and test their systems, not only for technical vulnerabilities but also for weaknesses in business logic.

For over 20 years, Securing has been helping the finance industry safeguard apps, networks, and services. If you’d like to discuss the security of your product or service, simply book a call or complete our contact form – we’ll get back to you shortly.